The shortest distance between us isn’t laughter. It’s a lip-smack.

Not those caused by noisy, open-mouthed chewing sounds when someone is eating. That raises a whole lot of other issues around table manners and disgust. For those of you who experience misophonia1, in which even the smallest sounds can become intolerable, you’ll be even more aware of that sound.

Nor is it the sort of weird, vibrating, slurping sound that Hannibal Lecter makes in Silence of the Lambs (director Jonathan Demme, 1991), just after he has described eating someone’s liver with ‘fava beans and a nice chianti’.

The lip-smack that I’m talking about here is the kind of sound we make when we don’t have food in our own mouths, but when we’re either watching someone eat or looking at food. What is curious about this sound is that it can seem like we’re invading someone else’s personal space or even, maybe, their bodily experiences. That just by making a sound with our lips, we’ve overstepped a boundary.

To see how this works, we’re first going to need to take a peek at the world of phonetics, ASMR and mukbang, monkeys and great apes. Hold on, this one is quite a ride.

Clicks, tuts, and lip-smacks

There’s a branch of linguistics called phonetics, which focuses on how we produce and understand the sounds that we make with our mouths, and the sounds themselves. One of the things that phoneticians have studied is what is often referred to as a ‘click’. It’s a sound that can be made when the tongue is pulled down sharply from the roof of your mouth, which in English is sometimes referred to as ‘tut-tut’ (or ‘tsk-tsk’ in American English). We might think that this is simply showing disapproval, but research has shown how their use is a lot more subtle than that. They allow us to respond audibly while not actually saying anything. It’s a useful thing that we can do in conversation when we know the other person expects some kind of affiliative response to a report of bad news, but we don’t necessarily want to say something that we might later regret2.

Clicks have, of course, long been known to be a central feature of some South African languages, such as the Khoisan languages. And they are found in English in a whole range of different settings: to chivvy along a horse, for instance, or alongside an audible in-breath just before we start to talk3.

There’s a whole range of cool names for these sounds that researchers use to help distinguish not only the sounds from each other but also how they are formed in the mouth. Those that are produced toward the middle of the mouth and/or using the palate are called alveolar clicks. Those that are closer to the teeth are called dental clicks. So, your average English ‘tut’ is probably more like an alveolar or dental click. Those that are more at the side of the mouth–to chivvy on the horse or call to your dog–they’re lateral clicks. When the lips are involved in making the sound, then they are called labial (or bilabial) clicks, and its these that are the closest to what we call lip-smacks.

They can sound like this:

or slower like this:

You may even be able to hear the lip movements in those sounds. Which brings us to ASMR.

The fine line between the senses and sensuality

It seems ironic that for all those people who experience misophonia or just feel disgusted at the sound of other people eating, that there’s a whole other bunch of people who find similar mouth sounds pleasurable. Sensual, even. I’m talking here about ASMR, or ‘autonomous sensory meridian response’ to give it its full title.

ASMR is a visceral response to certain sounds that can create a tingling sensation on the skin, particularly around the scalp and neck. The kind of sounds that can produce this sensation include whispering and those mouth sounds that involve the noisy parting of the lips, like a lip-smack (or bilabial click, if you prefer)4. They can also be considered relaxing or soothing rather than sensual. The painter Bob Ross has even been named as a source of ASMR sounds. It is his soft and gentle voice, accompanied by the quiet brush strokes of the paint on canvas, which can have a very calming effect on some people. Or you might just find his videos useful to learn how to paint.

The thing about ASMR and lip-smacking sounds is that they hint at something intimate. If you’ve ever heard about or watch mukbang, the Korean-originated phenomenon of live-streaming while eating large quantities of food, then you might see the connection there, too. There is something about ASMR and mukbang that suggests a closeness between the person in the video and the viewer. It’s not just that the person has to be near to the camera (and microphone) for it to pick up on those whispering sounds. It’s that the sounds themselves allude to bodily practices, like those made during eating or kissing, and that they draw attention to the lips, which are themselves involved in the same two activities.

It’s not as if we don’t use our mouths and lips to talk about more intellectual things. Like phonetics. But some sounds that we make with our mouths just seem more, well, bodily-oriented. So it is when we use them for other people that things start to get a little awkward. This is where we need the monkeys and apes.

Of apes and men

You may be surprised to learn that, at least as of early 2024, there is probably more research that has been conducted on lip-smacking in monkeys and apes (i.e. non-human primates) than there has been in humans. Or maybe you’re not, since we’ve tended to ignore these sounds at the edges of language in favour of words. Tut tut!

The thing is, lip-smacking has been observed across a range of primate species5, both in the wild and captivity, in both infants and adults. Rhesus macaque mothers have been seen using it with their infants to establish an emotional connection, producing the sound when they were looking directly at each other (‘mutual gaze’). Adult macaques have also been observed to respond to and sometimes reciprocate lip-smacks at a rhythm that is similar to human speech. In fact, even the facial and jaw movements needed to produce a lip-smack can look similar to the way our mouths move when we speak. In chimpanzees, lip-smacks have also been observed during grooming sessions by the chimp who was about to groom, well, let’s say a more vulnerable part of the body. Like a warning that nothing untoward is going to happen6.

We’re not alone, then, in making these lip-smacking sounds. As studies in the field of primate research develop, we have even more evidence of how they use these sounds to connect with each other, to console and affiliate with each other, and therefore to reduce the distance between themselves.

So now we’re ready to look at what happens in humans.

The rule of five (or three)

When infants begin to eat mushy or solid foods, it’s an intense time that demands constant surveillance and close interaction by the parent or caregiver. We often sit with our infant in front of us, helping to guide the spoon into their mouth, or at least watching while they learn how to use their hands and pick up food. It is during such moments, with an adult sitting close to an infant eating, that we can often observe the adult making lip-smacking sounds. And they often come in a series of five (or three) ‘beats’:

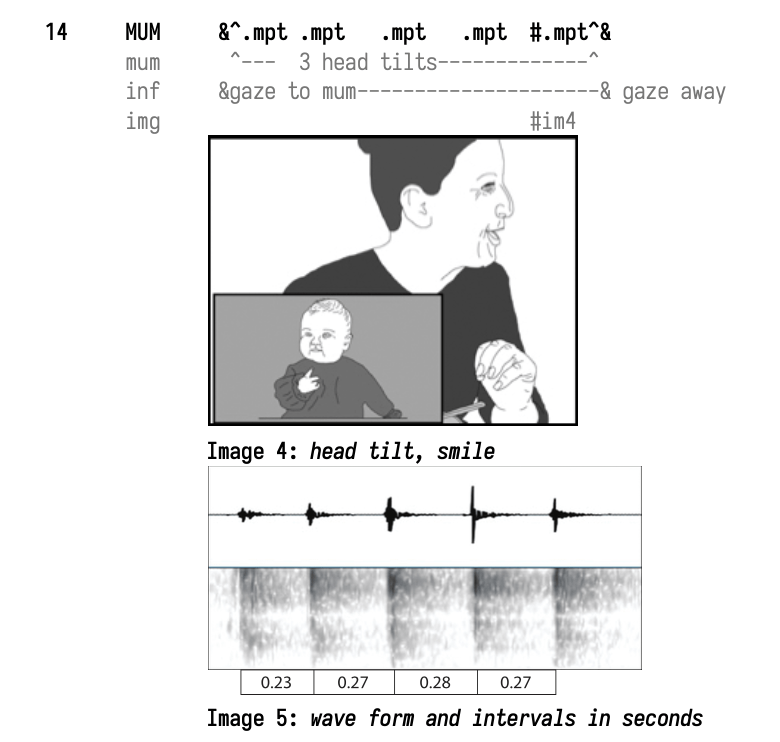

The image shown here is taken from a transcript of the first sound that we heard earlier with a rhythmical pace of five lip-smack beats or ‘particles’:

You don’t have to be able to understand all the symbols in the transcript to see that the wave form of those lip-smacks are pretty regular. Like the beats of music, with mouth movements that resemble chewing as much as they do eating. In a study of almost 400 lip-smacks produced by parents during infant mealtimes, the majority were produced in a chain of 5 beats, with the next most common pattern being a chain of 3 lip-smacks. I’m expecting you’ve tried this yourself by now. I find it almost impossible to write (or read) about lip-smacks and clicks without trying out the sounds for myself. My personal favourite is the lateral click (for the dog, of course).

It is not just the sound that is unique, here. Not only is there a rhythm and regularity to these lip-smacks, but they also work to attract the attention of the infant. What often happens is that the infant will look at the adult, and then start moving their jaw in a similar movement. In effect, it is as if the lip-smacks encourage the infants to chew, by imitating the motion and providing sound effects.

These sounds thus not only mimic those of eating but can be used to enact eating on behalf of someone else. As if we’re joining in with them. And that is why we could argue that they are the shortest distance between us, because it is as if we are eating for them, sounding their bodily practices. A similar thing happens when we make other sounds, like an emphatic mmm! when someone is eating or an oof! when we see someone hurt themselves. When we make these sounds at the same time that someone else is doing the movement, it is as if we are sounding on their behalf.

Now, there are times when this is really helpful: to show empathy, or to get involved with our infant as they eat. But the intimacy that it hints at could feel incredibly awkward in other situations. Just imagine lip-smacking while attending a formal dinner with colleagues or watching a stranger eating on a train. That’s just weird. Please don’t.

So there we have it. Lip-smacks are found in phonetics, ASMR, mukbang, and used by non-human primates as well as human primates. It’s such a curious and simple sound, but it can do so many different things. Use it wisely.

Research references

The following are the research papers that are referred to (in most cases, with a hyperlink) in the blog post:

Andersen, J. (2015). Now you’ve got the shiveries: Affect, intimacy, and the ASMR whisper community. Television & New Media, 16(8), 683-700.

Bennett, W.G. (2014). Some differences between clicks and labio-velars. South African Journal of African Languages, 34(2): 115-126.

Fedurek, P., Slocombe, K. E., Hartel, J. A., & Zuberbühler, K. (2015). Chimpanzee lip-smacking facilitates cooperative behaviour. Scientific reports, 5(1), 13460.

Ferrari, P. F., Paukner, A., Ionica, C., & Suomi, S. J. (2009). Reciprocal face-to-face communication between rhesus macaque mothers and their newborn infants. Current Biology, 19(20), 1768-1772.

Ghazanfar, A. A., Morrill, R. J., & Kayser, C. (2013). Monkeys are perceptually tuned to facial expressions that exhibit a theta-like speech rhythm. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(5), 1959-1963.

Keevallik, L., Hofstetter, E., Löfgren, A. & Wiggins, S. (2024). Repetition for real-time coordination of action: Lexical and non-lexical vocalizations in collaborative time management. Discourse Studies, (online first)

Keevallik, L., Hofstetter, E., Weatherall, A. & Wiggins, S. (2023). Sounding others’ sensations in interaction. Discourse Processes, 60(1): 73-91.

Keevallik, L., & Ogden, R. (2020). Sounds on the margins of language at the heart of interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(1), 1-18.

Ogden, R. (2013). Clicks and percussives in English conversation. Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 43(3): 299-320.

Ogden, R. (2020). Audibly not saying something with clicks. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(1), 66-89.

Rüdiger, S. (2022). Intimate consumptions: YouTube eating shows and the performance of informality. Internet Pragmatics, 5(1), 115-142.

Wiggins, S. & Keevallik, L. (2021). Parental lip-smacks during infant mealtimes: Multimodal features and social functions. Interactional Linguistics, 1(2): 241-272.

Wright, M. (2011). On clicks in English talk-in-interaction. Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 41 (2): 207-229.

- I might be obsessed with food, but the first time I read this I was sure they were talking about an aversion to miso soup. Turns out it’s a lot more troublesome than that. ↩︎

- Like when someone tells us a story about how they’ve been aggrieved, and we’re meant to show sympathy even if we don’t get what they’re so upset about. This kind of click is great for doing the minimum of showing support without having to use words that might then be misinterpreted, or which reveal that we weren’t really listening in the first place. ↩︎

- This is another useful feature of conversation, particularly when we’re talking in a small group. That audible in-breath sound, along with the ‘tut’ sound of the lips opening, can be an indicator that someone is about to speak. Useful when we’re trying to include other people in the discussion and want to be more sensitive to taking turns, but also when we’re trying to get our own words in. ↩︎

- Thanks to the wonders of the internet, there are thousands of videos where you can see people performing these ASMR sounds, should that kind of thing float your boat. I must admit to feeling out of my depth when I found these: I retreated to the safety of the monkeys, which we’ll hear about in the next section. ↩︎

- If we’re going to be really picky about this, then we might note that these lip-smack sounds are pretty variable across these studies. We could probably devise a whole new range of ‘click’ names for these as well. Some of them have even been seen to resemble speech. There are recordings of Geladas in the wild producing what has been called a wobble, which sounds unsettlingly close to human speech. ↩︎

- I have to say if I ever had a massage and the masseuse/masseur starting lip-smacking, I’m not sure I would find this reassuring in the slightest. Guessing it must be different for chimps. ↩︎

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0