There are many things that we learn when we eat with other people. One of these is that that we shouldn’t talk with our mouths full. That it’s rude, disgusting, and quite frankly can really turn you off someone. I’m not going to dispute any of these things. But I will show you that we do talk with our mouths full, just not in the way we expect. It’s going to involve Aragorn from Lord of the Rings and a bowl of stew. But first, we need to talk about talking.

Sounds at the edges of language

Talking is, of course, the way in which we use language to communicate with one another. I say ‘of course’ because if you couldn’t understand language (and, specifically, English) then you wouldn’t be reading this text. Language is commonly understood as being a system of signs and words, structured through grammar and syntax. There are, however, a whole range of sounds that lie at the edges of language, not quite words or signs, but which nevertheless are an important part of how we make sense of what each other is saying. These sounds are particularly crucial to understanding each other when we’re eating. Without them, we would not know that food tasted so good.

The sounds I’m referring to here can include anything from the ‘ahs’ we make when someone is telling us their troubles to the moans of frustration when someone plays a killer move in a boardgame. They include whistles, sniffs, and clicks (or ‘tutting’). We often make these sounds without necessarily noticing or realising that they occur, but they play an important role in the conversation, depending on where they are placed and who is making them. Academics have wonderful names for these sounds, the kind that make you feel intellectual just by saying them, such as non-lexical vocalisations, response cries, or liminal signs. For now, we’ll just call them sounds.

Eating talk is full of these kinds of sounds: from the mmms of pleasure to the yucks and ughs! or ew! of disgust. It’s the mmms that I want to talk about here (sometimes referred to as a ‘gustatory mmm’ in the academic literature to distinguish it from, well, other kinds of ‘mm’s, like the ones we make to acknowledge that we’ve heard what another person has said). It’s hard to represent intonation in textual form, but these mmms are usually emphasised and extended, with an up-down contour, as if we’re on a wave of pleasure: MMMmmm!. They are interesting because they are seemingly so obvious as a sign that we’re enjoying our food and yet they are so strategically placed in conversation that they say more about other people than they do about ourselves.

This is where we need Aragorn.

Timing is everything

There’s a scene in the extended version of the second film of the Lord of the Rings trilogy, The Two Towers, in which Eowyn offers a bowl of fish stew to Aragorn. For the LOTR fans, you’ll know which one I mean. For the rest of you, all you need to know is that Eowyn has a crush on Aragorn and she made the stew herself, which to be frank looks more like the overflow from a drain than food. It’s a watery mixture, a cloudy grey with floating lumps of dubious origin. Even in Eowyn’s own words, ‘it isn’t much, but it’s hot’. Despite this, Aragorn graciously accepts the bowl and proceeds to take a spoonful. As he puts it into his mouth, however, he realises that Eowyn is intently watching him. She wants to know what he thinks of the stew[1]. Here’s where the trouble lies: his response is just too slow. There is around a five to ten second delay after swallowing the food before he nods, then says quietly ‘mm….it’s good’. But by that time, we already know he’s lying.

The thing about sounds like mmm is that they need to be produced immediately after or alongside the other thing that they are apparently referring to. If we hurt ourselves, we utter the ‘ow!’ straight after the pain-causing event, and if we’re eating delicious food, the mmm should also happen while the food is still in our mouths. It’s easy to assume that this happens because the food is the thing that makes us produce the sound. That we say these things because we can’t help ourselves. That they are simply an involuntary response to something that happens to us: that the food is so good that we can’t help ourselves. Certainly, the adverts would have us believe that. But this is only part of the story. If these sounds were simply a case of the body ‘leaking out’ involuntary noises, then we’d be making noises all the time. Even when we’re alone.

What happens when we eat together, however, is that these mmms tend to happen at certain moments: when people are just starting to eat, when there’s a gap in the conversation, and when someone else has done the cooking. They serve a whole range of different social functions. With a timely mmm, we can show appreciation for the food, gratitude to the cook, and fill those awkward silences when we don’t know what else to say. Unlike words that we might use to express pleasure or to assess the food (such as, ‘its good!’, ‘its so tasty’), the important thing about the mmm is that it can be produced when food is in our mouth. And for that reason, if it is delayed even by a few seconds, it can appear false or contrived. There’s also an order to how we do these kinds of food assessments: an ‘mmm that’s lovely’ sounds much more authentic than ‘that’s lovely, mmm‘. The delay in Aragorn’s production of the sound is part of the reason why this scene is recognisably funny or awkward, depending on your perspective. It’s not just about how good (or bad) the food is or how it tastes, nor just about social expectations to be kind to the cook. The beauty of these sounds at the edges of language is that they do all of these things at once, in a matter of seconds. We can even do them to express pleasure on behalf of other people.

Sounding for others

When we’re eating with other people, these mmms are usually treated as an indicator of our own food pleasure. A spontaneous bodily reaction to the joys of flavour and texture. We typically don’t make these sounds when other people are eating, and if we do, the same logic usually applies: that the mmm is an expression of our own (imagined) pleasure, not theirs. This is where the boundaries between language and the body feel particularly thin. There is something apparently visceral in these non-lexical sounds that is partly about when they are produced (immediately) but also how: that they have prosodic features that exaggerate and stretch them in ways that are seemingly endless. There’s a sharp difference between a curt ‘mm’ that you might make to show you’re listening to someone and the elongated, up-down contour of the MMMmmm that we can make when we’re eating.

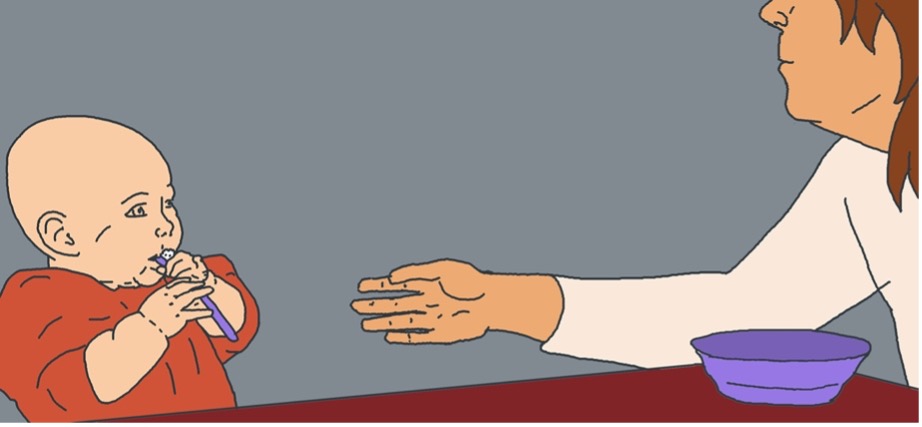

It’s this assumed ‘thin boundary’ that makes these sounds so tied to our own bodies. But when young parents are helping their infants to eat their first tastes of solid foods, they often make these mmm sounds even when they aren’t eating themselves. Regardless of whether an infant is using a spoon or their hands to eat, parents have been seen to produce the mmm sound at precisely the moment that an infant’s mouth closes around the food. The infant is eating, but in this case it is the parent who produces the sounds of food pleasure.

The timing here is impeccable, even if the parent doesn’t realise that they are doing it. It is so neatly placed that it feels almost choreographed: a synchronisation of two individuals to scaffold the eating practices of only one. This sounding for another while they are eating is an important way in which infants learn some of the basics of what it means to eat. And language is at the heart of this process.

A mouth full of sounds

So, talking with your mouth full is not necessarily about using words, but about the sounds (and gestures and facial expressions) that we make when we’re eating. If we did nothing other than just eat when we’re eating, our mealtimes would be much shorter and less interesting. That little sound that we make, the mmm of food pleasure, is just one example of a sound at the edges of language. These sounds that have for years been treated as ‘nonlanguage’, paralanguage, or even dismissed as childish or irrelevant, play a crucial role in how we eat together.

It doesn’t matter, then, if Eowyn’s stew really tasted that bad or if Aragorn was just trying to be kind. Whether we produce gustatory mmms because of how things taste or because of social norms or etiquette. What matters is that the timing and delivery of mmms is such that it allows us to believe that both options are equally possible.

[1] A similar thing happens when being given a gift: the right kind of response is important to showing that we genuinely like the thing that we’ve been given.

Research references

The following are the research papers that are referred (and linked) to in the blog post:

Dingemanse, M. (2020). Between sound and speech: Liminal signs in interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(1), 188-196.

Goffman, E. (1978). Response cries. Language, 787-815.

Hoey, E. M. (2020). Waiting to inhale: On sniffing in conversation. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(1), 118-139.

Hofstetter, E. (2020). Nonlexical “moans”: Response cries in board game interactions. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(1), 42-65.

Keevallik, L., Hofstetter, E., Weatherall, A., & Wiggins, S. (2023). Sounding others’ sensations in interaction. Discourse processes, 60(1), 73-91.

Keevallik, L., & Ogden, R. (2020). Sounds on the margins of language at the heart of interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(1), 1-18.

Reber, E., & Couper-Kuhlen, E. (2020). On “whistle” sound objects in English everyday conversation. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(1), 164-187.

Robles, J. (2012). Troubles with assessments in gifting occasions. Discourse Studies, 14(6), 753-777.

Wiggins, S. (2002). Talking with your mouth full: Gustatory mmms and the embodiment of pleasure. Research on language and social interaction, 35(3), 311-336.

Wiggins, S. (2019). Moments of pleasure: A preliminary classification of gustatory mmms and the enactment of enjoyment during infant mealtimes. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 1404.

Wiggins, S., & Keevallik, L. (2021). Enacting gustatory pleasure on behalf of another: The multimodal coordination of infant tasting practices. Symbolic Interaction, 44(1), 87-111.

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0