It’s a dangerous thing to say, that you like a particular type of food. It can lead you into all kinds of trouble. Like that one time you said you liked liquorice1 to show gratitude for a gift and now the same person continues to give you liquorice because they think they’re being kind. Maybe even the news got out and others give you liquorice too, because they know you like it. To admit otherwise would be like kicking a puppy. Better to keep receiving that liquorice with a smile, for the months or potentially years that this will continue.

The same applies when you say that you don’t like something. It’s even more dangerous, perhaps. You might never be offered that food ever again.

Take the example of the scene in the film The Imitation Game (director Morten Tyldum, 2014) in which one of the main characters (Alan Turing) is invited for lunch with work colleagues. Except it isn’t a direct ‘would you like to join us for lunch’ invite, it’s a ‘we’re going to get some lunch’ sort of invitation2. It ends not with an acceptance or refusal but rather a statement from Alan: “oh, I don’t like sandwiches”:

This clip is, amongst other things, an excellent example of how conversation often relies on shared understandings of words that aren’t always, well, shared. The upshot is that Alan doesn’t go for lunch and his declaration about not liking sandwiches means that they might never invite him again.

Liking or not liking food has become such a driving force of our eating practices that it traps us in situations that are resistant to change. Which is why I don’t like food anymore. I still enjoy food. I’m just trying to avoid saying the words ‘like’ or ‘don’t like’ when it comes to assessing food. It is because the language traps us. And this is how it works.

How food likes came to be a thing

The concept of food dis/likes has been around for decades. They are sometimes referred to as ‘food preferences’ though that term refers to a comparison between different foods (as in, “do you prefer this food or that one?”) rather than a rating of the food itself. In a moment, we’ll return to how food dis/likes are measured but for now, it’s worth taking a brief trip back to some of the earliest work to see just how ingrained this concept is.

In 1938, Karl Duncker3 conducted a study about how children might be influenced in their food preferences through ‘social suggestion’: either by watching older children or through being told stories about the food. The study involved children between 2 and 5 years old, who were presented with the following foods: carrots, bananas, nuts, apples, bread, and grapes. They were then asked to choose “which one they liked best” when they were on their own or with another child. What Duncker found was that younger children more readily imitated the older children than vice versa, and that this peer influence was much stronger when the children were friends. In social situations, therefore, we can be swayed by the actions of other people. We may never know if the children’s really did like that food best, but the important part is that they changed how they responded based on the actions of others.

In the conclusion of the article, Duncker reflects on a personal experience in which, as an adult, we might be able to change our food dis/likes:

The study is an example of how, almost 90 years ago, food dis/likes were already treated as a concept that can help us to understand eating habits, particularly in children. Another study, a few years later in 1946, tracked the food preferences and consumption of 2- to 3-year-olds over the period of a year, examining how children might learn to like different foods during this period. Even at this early stage4 in eating research, therefore, it is an indication of how the idea that we have likes and dislikes was firmly established. More importantly, the words ‘food likes’ and ‘food dislikes’ were themselves already part of the lexicon of eating.

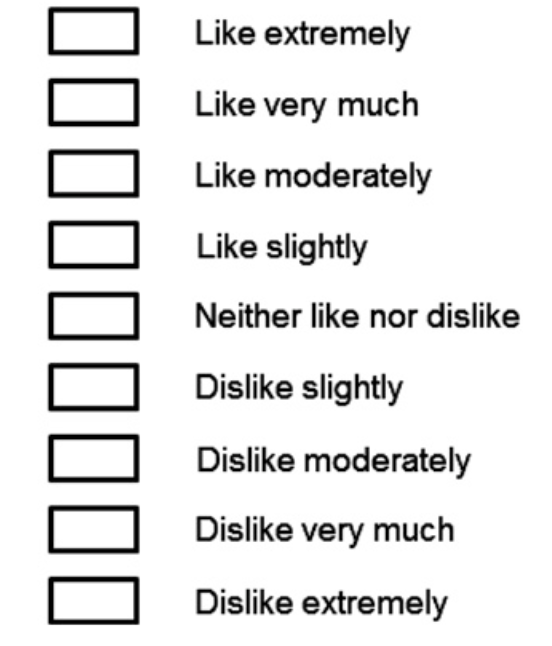

It was, however, an interest in soldiers‘ rather than children’s food preferences that sparked the development of a measure of food dis/likes. In the aftermath of the second world war, the Quartermaster Food and Container Institute was established in Chicago and became a powerful centre of food research that has remained incredibly active and prolific since then5. The vast sums of money spent on providing food for military personnel meant that it was important that they liked the food and would actually eat it; the economy depended on it. In an attempt to devise a very simple method of measuring soldier’s food dis/likes, David Peryam and colleagues developed what became known as the 9-point hedonic scale, and has since become one of the most well-established means of measuring food dis/likes in eating research world-wide. It looks like this:

That’s it. It’s deceptively simple, having been designed to be understood quickly and to determine the degree to which people like or don’t like that food. The labels of each of the ‘points’ (or boxes, as in the image above) are then converted into numbers before any statistical analysis can be carried out, with 9 representing ‘like extremely’, and 1 representing ‘dislike extremely’.

This is where we start thinking about words versus numbers, and the difference between the two.

Numbers, labels, and other categories

Being able to determine how much you like a food on a rating scale has proved to be a robust measure of food dis/likes under experimental conditions, that is, when people are tasting a food in a laboratory or setting in which many other factors can be controlled. But deciding that you ‘like moderately’ a food might not necessarily be the same as saying it’s a 7/9 on a numerical scale. A study examining ratings of chocolate has shown this to be the case under experimental conditions, with people rating the chocolate differently depending on whether numbers or words were used. The chocolate or their enjoyment of it hasn’t changed, but the measurement has. We rate food differently depending on whether we’re using numbers or words.

When we consider how we talk about food dis/likes in everyday life, outside of the laboratory, the words we use have a greater significance. They are the way in which we make sense of not only our eating habits but also those of the people around us. We become known through the things we like, from our hobbies to our music tastes. You probably know the food dislikes of your loved ones even more clearly than you know their food likes or loves. But it’s a certain kind of knowledge. Our own food dis/likes are what might be described as a ‘Type 1 knowable’, something that only we can claim to know because it relates to knowledge that only we, technically, have access to, like our mental states, emotions, or bodily experiences. We can tell other people about these things and they can know them as an observer, but they can’t know them in the same way that we do.

It becomes knowledge about us because we often state a food dis/likes in the following form:

“I don’t like sandwiches”

While the assessment might change–we might love or hate sandwiches for instance–in this case, the food being referred to is a general category rather than a particular item (in which case, we might have said ‘I don’t like this sandwich’). This way of talking about food dis/likes is what has been referred to as a ‘subject-side category assessment‘ and the effect that it has is to imply that this is something that goes beyond the here-and-now. That the not liking sandwiches applies, regardless of the time and place. That it’s a knowable thing about the person who said it and it has consequences. Alan doesn’t like sandwiches so we don’t need to invite him for lunch again.

The thing is that it pins down what is rather a fluid, dynamic process (how we taste and experience food) into a single word or words. When we talk about not liking sandwiches in this way, as a category of food, it becomes a label that defines who we are rather than what we are doing. The label sticks and becomes difficult to shift. We hold each other accountable for changing, like if we suddenly professed to liking sandwiches when we previously said we didn’t like them. Or to not liking liquorice after all.

Changing words to fit people, not people to fit words

We can still enjoy our food, regardless of what and how we eat, of which food makes us smile and reach for more, of which we avoid or cannot tolerate. What needs to change is the words that we use to describe eating rather than trying to change ourselves to fit the words that have already been said.

Among the many hurdles that impede attempts to change our eating practices are the words that have become ingrained in our lexicon. The longevity of food preference research and the robustness of the word “like” in everyday parlance means that these words are probably with us for some time yet. But we can adapt them so that they do the things we need them to, without trapping us in situations that are resistant to change.

Small adjustments in the words are all that is needed:

- “don’t like” could become “not liking” to shift it slightly from a fixed state to one that is potentially more changeable,

- “enjoy” rather than “like” because the former word still captures the pleasure but doesn’t necessarily fix it into a label,

- adding a time period or other element: “I don’t fancy a sandwich at the moment”, or “I haven’t developed a taste for liquorice yet”

From now on, I’m going to try to say that I’m enjoying (or enjoyed) my food rather than I liked it. To situate it in the here and now, to avoid it becoming a label that then traps me into certain ways of eating and stops me from exploring new foods. Like the many varieties of liquorice.

As for what happens when it’s children who say they don’t like it, well, that’s a story for another day.

Research references

The following are the research papers that are referred to (in most cases, with a hyperlink) in the blog post:

Duncker, K. (1938). Experimental modification of children’s food preferences through social suggestion. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 33(4), 489.

Lamb, M. W., & Ling, B. C. (1946). An analysis of food consumption and preferences of nursery school children. Child Development, 187-217

Meiselman, H. L., & Schutz, H. G. (2003). History of food acceptance research in the US Army. Appetite, 40(3), 199-216.

Nicolas, L., Marquilly, C., & O’Mahony, M. (2010). The 9-point hedonic scale: Are words and numbers compatible?. Food quality and preference, 21(8), 1008-1015.

Peryam, D. R., & Pilgrim, F. J. (1957). Hedonic scale method of measuring food preferences. Food technology.

Peryam, D. R., & Haynes, J. G. (1957). Prediction of soldiers’ food preferences by laboratory methods. Journal of Applied Psychology, 41(1), 2.

Pomerantz, A. (1980). Telling my side:“Limited access’ as a “fishing” device. Sociological inquiry, 50(3‐4), 186-198.

Wiggins, S. (2014). On the accountability of changing bodies: Using discursive psychology to examine embodied identities in different research settings. Qualitative Psychology, 1(2), 144.

Wiggins, S. (2014). Adult and child use of love, like, don’t like and hate during family mealtimes. Subjective category assessments as food preference talk. Appetite, 80, 7-15.

- Liquorice connoisseurs will be well aware that there is huge variety in this area and that not all liquorice is equal. The kinds you get across the Nordics and the Netherlands, for instance, are a world apart from the abomination that was ’Bassetts Allsorts’, circa 1980s Britain. As a novice in the liquorice domain, I have much to learn. ↩︎

- If you’re interested in how conversation works in these kinds of ways, I highly recommend Emily Hofstetter’s youtube videos (“EM does CA”) such as this one on how we can do the same action (such as an invitation) in different ways. ↩︎

- A deep-dive into some of Duncker’s other research is well worth it in itself, since it is his work on the ‘candle problem‘ and what he termed functional fixedness that inspired the phrase ‘thinking outside the box’. ↩︎

- There has been other eating research earlier than this, particularly on hunger and satiety, but that needs an empty stomach before you can read it. Trust me on this one, it is grim reading in places. We might save that one for another blog post. ↩︎

- If you’re interested in the history of food acceptance research, I highlight recommend this detailed and fascinating account. Its an eye-opening account of just how much of our current knowledge of eating practices, alongside established theory and methods in the field, originated from two research centres that are funded by the US army. ↩︎

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0