It is that time of year again. In between all the busyness, the preparations, the rushing to get things finished, the travelling, the inevitable coughs and colds, and the worry that we didn’t buy the right presents, is the one thing that might just send us over the edge.

Yes, it’s the shared meals. The get-togethers. The work lunches and dinner parties. The meals with all the family. The sitting down at a table from which you are effectively trapped for a considerable amount of time and much longer than it takes to ingest the food. While we can be glad of the food and the company, and the privilege of having meals prepared for us, it is the conversations that we might dread. What are we going to talk about? We’re either going to have to talk to people who we may not know very well and don’t know what to talk about, or else we do know them and may want to avoid certain topics of conversation. Like this scene from the TV series Fleabag (Creator: Phoebe Waller-Bridge) and the loaded questions. You look well, where here have you been? or We thought you couldn’t have them?

Well, this is awkward

For the record, can I be crystal clear that I’m not talking about my own family or work colleagues–they are all delightful, of course–but rather about the kinds of situations that we might find ourselves in. At any time of year. They are those occasions that are a bit more ceremonial than usual; they bring people together to share a meal who are most likely not our regular dinner companions. They carry with them a different set of expectations.

It is during these shared mealtimes that we are often required to engage in what is known as ‘small talk’. Except that it isn’t small at all. It eludes many of us and can become a bigger concern than the dress code and the food options. As the subject of thousands of videos on social media, it appears that I am not alone in wondering how to hold a dinner conversation. There is as much etiquette around this as there is around how to hold a fork and who gets to eat the last piece of cake. There is guidance on which subjects are taboo or off-limits, on conversation starters and icebreakers. Even as someone who researches mealtime interaction, I am no better at this than anyone else. Much as I enjoy shared meals and celebratory events, figuring out what to say (and how to say it) is still something that takes up far more head space than it probably should.

This blog post is therefore about small talk during mealtimes and why it is so difficult to do. I can’t promise that you’ll be any better at small talk by the end of it, but you should at least have a clearer understanding of why the struggle is so real.

Mastering the art of mealtime charisma

It is a strange notion that the kinds of conversations we have around mealtimes are of a different sort to the kinds that we might have elsewhere1. Or that in some situations it may not be appropriate to talk at all during a meal. As many of us are wondering how we can sharpen up our dinnertime chat, it might be of interest to know that back in the late 1970s, two researchers conducted a study on exactly this topic.

In 1979 in a small, midwestern US city, Jacque Jewett and Hewitt B. Clark set out with the aim to develop a training program to make dinnertime conversation “more mutually interesting”. Armed with a large bag of cookies2 and the sort of optimism only surpassed by team-building gurus, Jewett and Clark embarked on a study that, quite frankly, would not look out of place at a corporate training event.

What made this study unique was that the people being trained were 5-year-old children.

That’s right, at an age when most of us might be happy enough making a mountain out of our mashed potatoes3, these kids were mastering the art of mealtime charisma. The study was not about making things less awkward for the children (or their parents) but rather as a way for them to get more involved. While many of us are no longer five years old, it raises questions about whether we can be trained to be better at mealtime chat and what it actually means to talk at mealtimes. There were just four children trained in this study and they were given the false names of Meg, Ben, Dan, and Ken.

This is what happened.

Bootcamp for small talkers

The study began by investigating the usual family mealtime as a baseline condition, before any training began. Parents were provided with tape recorders (it being the late 70’s, this also meant that it was audio only, a point we’ll come back to later) to record each dinnertime. They were also asked to complete a checklist about their child’s behaviour during the meal, containing questions such as “Did your child talk with his/her mouth full?” and “Did your child ask Mother about work?”. All this material was then returned to the school the following day, and, after training had begun during the coming weeks, these conversations would be scored according to the kinds of comments that the children made. The kids would then be quizzed on their performance and the teachers could check if they reported accurately on what they had said at the previous evening’s dinner. If they did, they received a cookie.

Meanwhile, training at preschool began. The children took part in one-on-one communication coaching with their teachers as well as simulated family-style lunches in which they could practice their newly acquired skills together. During the coaching, the teachers would model the kinds of questions that children could ask and use prompts to help the children develop their conversational dexterity. They provided follow-up questions, for instance, as well as encouraging and praising them when they said something correctly. The simulated lunchtimes then placed teachers in role-play format as substitute parents, and training focused specifically on topics related to work (with parents), school (with siblings), and appreciation (e.g. complimenting someone).

Now I don’t know about you, but that sounds pretty intense for five-year-olds. I’ve had less demanding courses as an adult for learning a new language. While I might have had practice in role-play and received feedback on my grammar4 and pronunciation (usually along the lines of ‘has room for improvement’), my training never included recording actual conversations nor having to report back and being graded for the accuracy of what I could remember about what I said. Not enough cookies, either.

So how did Meg, Ben, Dan, and Ken do?

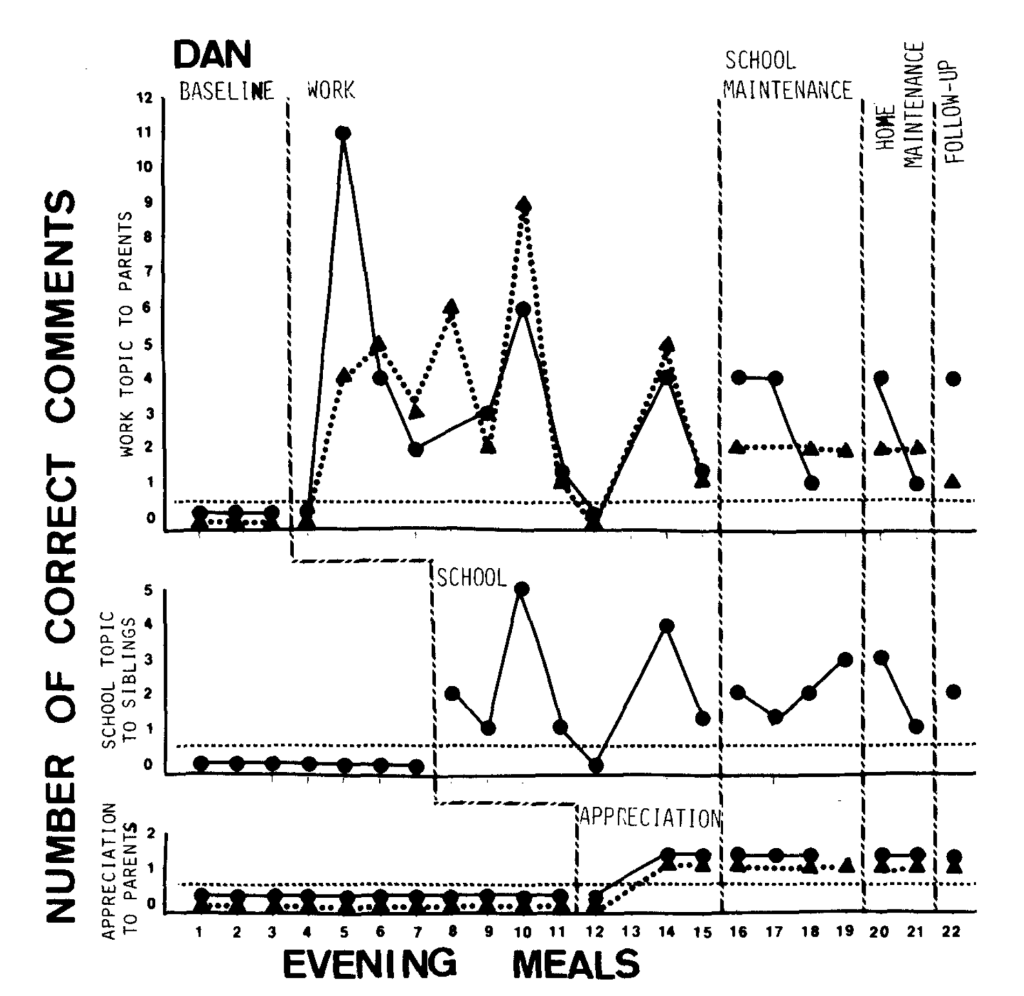

Once training had started, they all met the target of making appropriate comments about work and school issues, at least during some of their family dinners. Dan seemed to excel in his conversational skills, saying the right things across many of his mealtimes during the study and to some extent even after training had ceased (see the figure below which charts his contributions across the 22 days; the word ‘maintenance’ here refers to what happened after the training). There were, however, very few appreciative comments from the children. The training worked in terms of asking questions about work and school, but showing thanks or complimenting others seemed to be a more elusive skill.

The parents themselves reported that the training had enriched their mealtimes and made the conversations more enjoyable5 for their children and, in all but one case, themselves. There was some variation across the kids, of course. Dan and Ken continued in the study the longest–for about 3 weeks–whereas Meg was involved for only around two weeks (due to “withdrawal from school near the end of term”6). The conclusion of the study was that the procedure could help to make meals more enjoyable and that children can be trained to be better conversationalists. Even if we didn’t get to hear the children’s version of events.

My concern here, however, is not to pick holes in a study that seems to have been carefully and thoroughly conducted, and which in many ways surpasses much of what is published today. But it serves as an example of how difficult it is to do small talk and how we lose so much if we just focus on individuals asking questions.

Everything, everywhere, all at once

The thing about mealtime conversations is that we are usually talking to more than one person at a time. Or that multiple conversations are occurring simultaneously. I’m excluding here those heart-warming chats you have with a treasured friend or loved one over food or drink, or any one-to-ones for work or leisure7. As soon as we have a shared meal that involves four or more people, then we have the potential for multiple conversations. Interactional researchers refer to these as multiparty interaction: where there are many persons (or participants) who are co-present and, at times, interacting in the same space. It is therefore never as simple as striking up a conversation with only one person; often we’re talking to, and telling stories with, several people at once. Dinnertime talk is therefore a bit like dancing at a ceilidh: we never know who we might be interacting with next or whether the conversation will quickly build up speed or dwindle away.

We then have to consider that a conversation is not just about what we say. It is also about what happens with the rest of our bodies: our eye gaze and hand gestures, the handling of food and drink, and the way our bodies are positioned in relation to other people. This is what is known in the field of Ethnomethodology and Conversation Analysis (EMCA) as multimodality8; in other words, that we use various resources to interact with other people in a social setting, not just our voices. We are not simply talking heads. These multimodal ways of interacting are intricate and complex, and as research in this field develops, we learn more about just how complicated and intertwined it really is. Such as how we manage to integrate drinking while talking.

When we start to consider dinnertime conversations in this way–as multiparty and multimodal–then we can begin to understand what it is that makes them, at times, so tricky. It was never really about small talk after all. It was always the bigness of interaction. The preschooler study couldn’t have hoped to capture any of this because it only ever recorded the audio9 and it predates much research about preschool interaction and mealtime talk. All the varied ways in which we show appreciation and understanding–through nodding, smiling, and sharing eye gaze at just the right moment, for instance–will be missed if we only consider the words that are uttered. Or, conversely, that eye gaze can be as controlling as it is empathic, and that even very young children learn to recognise “the look” from an adult as doing something much more than a mere glance. More importantly, that it is how these various modes of interacting are intertwined in ways that cannot be clearly separated into verbal and non-verbal behaviours.

It is because of the interconnected nature of multiparty, multimodal interaction that we need to go beyond the level of training individuals how to ask questions. As the Fleabag clip illustrates so eloquently, we can never be sure where a conversation will lead or when a new question might catch us by surprise. That it is not just about asking questions but also knowing how to respond to them. That we tell stories and create shared narratives (not for us, thanks). That assessments (and judgement) can be hidden in questions (It’s going well, is it?). That sometimes overlapping talk is okay (or not, as an interruption) and that there is no time out from interaction. These principles are the same whether we are adults or children, family or not.

This is not just like learning a new language. It is like learning to dance.

Are you ready to dance?

While it might be tempting (and, for some, lucrative) to suggest that we can be trained to be better dinner conversationalists, this grossly underestimates the complexity of interacting with other people. Training individuals only works if we are behaving as individuals. But we’re not; we’re interacting with others in a multiparty, multimodal way as if in a dance. Our questions are only as good as how people respond to them, our conversational wit dependent not only on our delivery but also on how this is received and how it plays out in the continual flow of the interaction. Dan might have received a score for asking his Mum about her work but this tells us nothing about the rest of the interaction or what happened with the other family members. Or that we can become involved in our mealtimes in ways that go beyond just asking questions.

It was thus never small talk. Whether we are five or fifty, with family or friends, our mealtime chat is as much, or perhaps more, about the unique blend of people, food, and setting than it is our ability to ask questions and listen politely. Sometimes we are well-matched with our dancing partners and the music hits the spot, sometimes not. The important thing is to keep dancing until it does.

Research references

The following are the research papers that are referred to (in most cases, with a hyperlink) in the blog post:

Brumark, Å. (2003). Narratives in family dinner table conversations: A study of the co-narration at dinnertime in twenty Swedish families. PhD dissertation. Södertörns högskola.

Hoey, E. M. (2018). Drinking for speaking: The multimodal organization of drinking in conversation. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 1(1), 10-7146.

Jewett, J., & Clark, H. B. (1979). Teaching preschoolers to use appropriate dinnertime conversation: An analysis of generalization from school to home. Behavior Therapy, 10(5), 589-605.

Kidwell, M. (2005). Gaze as social control: How very young children differentiate” the look” from a” mere look” by their adult caregivers. Research on language and social interaction, 38(4), 417-449.

Korobov, N. (2011). Mate-preference talk in speed-dating conversations. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 44(2), 186-209.

Mondada, L. (2019). Contemporary issues in conversation analysis: Embodiment and materiality, multimodality and multisensoriality in social interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 145, 47-62.

Ochs, E., Taylor, C., Rudolph, D., & Smith, R. (1992). Storytelling as a theory‐building activity. Discourse processes, 15(1), 37-72.

Stokoe, E. (2010). “Have you been married, or…?”: Eliciting and accounting for relationship histories in speed-dating interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 43(3), 260-282.

Visser, M. (1992) The rituals of dinner: The origins, evolution, eccentricities, and meaning of table manners. Penguin Publishing Group.

- If you are curious about this topic, then Margaret Visser’s (1992) The Rituals of Dinner is the book to read. ↩︎

- Before we start getting concerned about the ‘sweets as reward’ thing, consider that the study was conducted in the late 1970s and the evils of sugar were not yet so apparent (nor perhaps, the cookies so loaded with sugar and palm oil as they typically are now). ↩︎

- See ‘Play by the Rules’ blog post. At this rate, mashed potatoes are going to get a mention in most of these blog posts. I’m so sorry about this. Must have been some fixation as a child. ↩︎

- In my defence, I am amongst that section of the English population who missed out on grammar due to some strange educational policy that argued that we simply needed to encourage kids to get words down on paper and worry about the structure of everything later on. Creativity over rules and regulations, I guess. That is why I learnt more about English grammar while learning other languages and why I’m still learning to this day. ↩︎

- How the researchers measured this enjoyment or how the parents themselves understood how much their children enjoyed the conversation, is not at all apparent. Enjoyment is a notoriously tricky thing to understand, let alone measure, so I suggest we take that finding with a hefty pinch of salt. ↩︎

- Again, no further information on this, but I like to think that Meg’s parents took her for a well-earned holiday after an intensive period of training. ↩︎

- If you’ve got a date coming up, then you could do worse then read some research on speed-dating, such as this one or this. ↩︎

- There is also another field of research that is called multimodality, building on the work of Gunther Kress, and probably various other researchers who use the same term to mean something quite different. In still other areas of the social sciences, this is sometimes referred to as nonverbal behaviour or nonverbal communication, but again the ideas behind these words are very different. This is how it goes in academia, I’m afraid; we all talk slightly different languages and it is easy to get confused even when we use the same words. ↩︎

- Having conducted my earliest research in the late 1990’s, and when tape-recorders were the cheapest and most portable device I could get my hands on, I know how much you miss when you only have the sound. ↩︎

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0