In the Museum of Rural Life, in East Kilbride in Scotland, there is an old farmhouse that has been preserved to portray life as it was, dating back to at least the 1950s. I was always drawn to the farmhouse kitchen, fascinated by the ways in which the room could provide a glimpse into daily routines. Reminded again about how easy we have it with electricity, running water, and drawers full of gadgets.

It was, however, the porridge drawer that got me. That’s right. A porridge drawer.

I remembered the drawer when I was wondering recently if having porridge for dinner constituted a proper meal. Like, just for me, when the rest of the family were elsewhere. When something simple and comforting is called for. Then I realised just how strong the notion of a ‘proper meal’ can become embedded in how we justify our food choices, whether we are cooking for other people or only for ourselves. That we rarely cook just ‘a meal’ but something that has to fit certain social or cultural requirements.

But we need to get back to that drawer.

The porridge drawer

Of all the things that you could imagine can be kept in a drawer, I’m guessing that porridge would be pretty far down the list. The idea, however, is this… Actually, I should include a trigger warning here. For those of you who don’t eat porridge or, quite frankly, think it totally unappealing, then you might get even more grossed out by this… after cooking a large pan of porridge, what was not eaten straight away was poured into a wooden drawer (lined with cloth or tin) for the porridge to cool. Over the next few days, the set porridge could then be sliced and eaten as a portable snack. There is, of course, some discussion about the veracity of this idea, though it appears to be a genuine Thing, and something used in crofting and farming homes across Scotland and elsewhere. It was even the focus of The Broons1 comic strip.

Now, like me, you probably have questions. Like how we would recognise a porridge drawer if we saw one. Surely it looks just like any other drawer until, that is, you pour in the porridge. You might just be feeling slightly nauseous at the thought of eating food from a drawer, along with the bits of fluff and random junk that collect in the corners of wooden furniture.

The point, however, is that the porridge drawer is potentially evidence of 20th century snacking. We’re talking long before pop-tarts were invented. So, when we talk of how families used to always sit down together to eat a ‘proper meal’ and bemoan that it just isn’t like that anymore, well, maybe it wasn’t always that way. That sometimes, a slice of cold, congealed porridge for your ‘piece’2 was the closest you got to eating with the family.

Which brings me back to the issue of what we mean by a ‘proper meal’.

Lasagna for breakfast

The thing about eating talk is that it is often talk about meals. That we don’t just ‘eat’ but that something else is going on when we’re eating: the meal is an event that encompasses the eating but involves so much more. These meals then have different meanings, structures, and expectations that distinguish one kind of meal from another. Such as when we talk about ‘proper meals’ rather than a ‘snack’ or ‘quick lunch’. This meal talk then becomes a thing that holds us accountable for how we eat.

It was anthropologists– Mary Douglas in particular–who first presented the idea of meals as having not only a structure but a kind of coded language that could tell us, amongst other things, about the kind of meal it is and the occasion that it represents. For example, Douglas argued that a proper meal has an ‘A + 2B’ structure, with A representing the ‘stressed’3 course (like the main course) and B the two ‘unstressed’ courses (like starter and dessert). Within each course, then there might typically be ‘a +2b’ elements. This could be, for instance, fish (a) + potatoes (b) and broccoli (b). Or ice-cream (a) with chocolate sauce (b) and rainbow sprinkles (b). See, research backs me up on this one, sometimes you need the sauce as well.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that you have to eat according to this pattern. Nor that we always do. I’m guessing many of us don’t have the kind of lifestyle (nor financial situation) in which we eat a three-course meal for every ‘proper meal’. Douglas’ work was also based on a sub-section of the population: an affluent part of British culture in the 1960s and 1970s. But more recent research from around the globe nevertheless confirms that there are expectations and social norms around what meals should consist of, and what foods are appropriate for each meal. It is not just that these norms exist, but that they can be used to hold us accountable for what we eat.

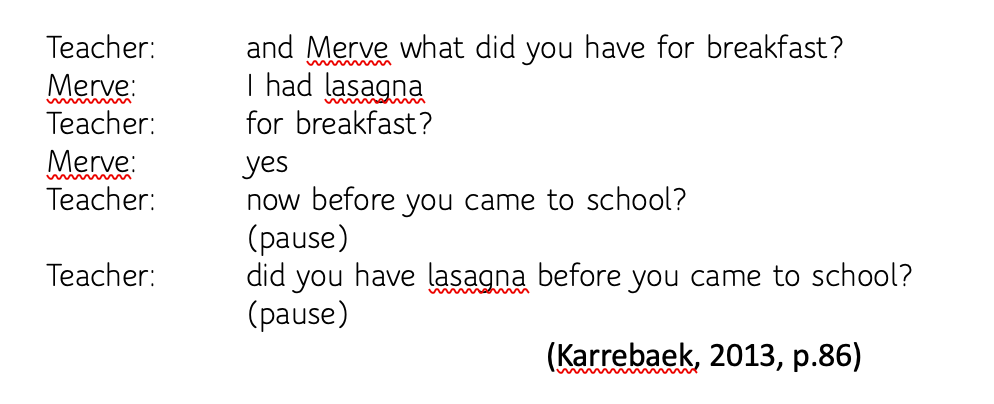

Take the following example, from a study of children in a Danish kindergarten class, researcher Karrabaek shows how one child was repeatedly questioned about her choice of breakfast:

It is not just that the teacher sounds slightly incredulous (‘for breakfast?’) when Merve first answers her question, but that they continue to ask about the lasagna as if the first answer was not sufficient. What happened next was that other children started to get involved, asking things like whether it was eaten hot or cold, and so the pressure on Merve remained. While an uncomfortable piece of conversation, it is a stark reminder of how norms about ‘proper meals’–or even just acceptable meals–are not just abstract ideals. They become part of our daily lives through the ways in which we talk about them. Our eating talk is used to question others, to become something that we need to justify and explain.

Clearly, context is everything. Karrebaek’s study was based on a kindergarten class with young children. Had it been a group of friends talking after a party the night before, well, that might have been a different kind of conversation.

Whether we eat lasagna for breakfast or porridge for dinner is not an issue, therefore, if we’re an adult and on our own. In those situations, quite frankly, eat what you can. It is when children and families are thrown into the equation that people start to become more concerned. Because then we’re into the realms of not just what is a proper meal, but what counts as a proper family meal. This brings us back to the Broons.

Proper meal = proper parenting

In The Broons comic strip above, the second panel shows most of the family eating porridge together for, presumably, breakfast. It portrays an idealistic notion of a family meal, sitting at one table, eating together, even if some of the kids are complaining about eating porridge rather than cereal. It is reminiscent of some of the classic research on family meals from the 1980s where the ‘cooked dinner’ was described in interviews with mothers as being the epitome of a proper meal. The classic version of this is some form of meat/fish, potatoes, and a vegetable (or ‘meat and two veg’ if you count the potato as a vegetable rather than a starch).

That’s all well and good if you have the time and resources to buy and prepare all these foods on a regular basis. But it’s a fairly high standard to maintain on a regular basis. Expectations of meeting these standards can add an additional pressure if you don’t have the financial means to support it. Moral obligations to provide for the family in this way are not only experienced by mothers but also by other caregivers. In a study of families in a working-class area in England, fathers reported that it was not simply a case of providing a proper meal but ensuring that the kids would actually eat it. As one of the participants in the study said: “It’s working out a compromise all the time … what is a good proper meal to what we can get down their necks. You can shove a proper meal in front of them every time; if they don’t eat it, it’s not a proper meal.”

Of course, it’s not just about money. In dual-earner families, it can be the synchronisation of the schedules of family members, whether for work or leisure activities, that can determine the form and frequency of meals together. After-school clubs, sports activities, youth organisations: there can be a lot to fit in. In our own household, we’ve even been known to plan our meals around the dog4.

When we talk about making a proper meal for our families what we’re doing is showing that we’re doing proper parenting. Justifying ourselves to other people that we’re good enough parents, the kind of people that care for our kids regardless of our financial situation or family circumstances. It’s a moral expectation, a way of talking about meal provision that is used to manage our own identities as being a good enough parent. The sociologist Marjorie DeVault provided a rich account of how some of these moral obligations are embedded in the invisible work of domestic labour in her book Feeding the family. It is through family meals that we do being a family, DeVault argues, through the unspoken interactional and emotional work of ‘performing’ a family meal. She even refers to a similar idea in Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse:

“Later, at dinner, Mrs. Ramsay accomplishes two tasks: in addition to supervising the preparation and service of the food, she brings the diners together so that they experience the meal as a particular kind of event. Neither of these tasks is sufficient without the other, both are essential to the creation of a ‘dinner’.” (DeVault, 1991, p. 6)

For the love of porridge5

It is never as simple, therefore, as just making a ‘meal’. The social and moral norm to prepare proper meals is pervasive across different cultures and households. It has become a thing not only to define how we eat but also to define who we are: that we are the kind of person that prepares those kinds of meals for other people. That it is not only the meal that is proper, but also ourselves. This is not about nutrition, it’s about identity and moral accountability.

Even when we eat only for ourselves, we may feel the pressure to do otherwise. At the start of this blog post, I described porridge for dinner as a rare occasion, just for me. When we explain why we aren’t having a proper meal we usually have to do some work to justify it. That we just want ‘something simple’, a low-fuss alternative. The alternative to the proper meal is not an ‘improper meal’, exciting though that sounds, but something that is often down-graded from a meal to a snack, a light-bite, or a quick lunch.

It is perhaps time to change the script. Talking about proper meals is not going to make us or our kids any healthier. Nor is it likely to help us adapt to more sustainable eating practices. At best it gives a sense of pride and status, at worst it is used to vilify people who are already struggling in a system that keeps pulling them down.

In the spirit of breaking these norms and in support of Merve, then, I’ll eat porridge for dinner if I want.

Research references

The following are the research papers referred to above (in most cases, with a hyperlink):

Brannen, J., O’Connell, R., & Mooney, A. (2013). Families, meals and synchronicity: eating together in British dual earner families. Community, Work & Family, 16(4), 417-434.

Bugge, A. B., & Almås, R. (2006). Domestic dinner: Representations and practices of a proper meal among young suburban mothers. Journal of Consumer Culture, 6(2), 203-228.

Charles, N., & Kerr, M. (1986). Eating properly, the family and state benefit. Sociology, 20(3), 412-429.

Douglas, M. (1972). Deciphering a meal, Daedalus, Vol 101 (1): 61-81

DeVault, M. L. (1991). Feeding the family: The social organization of caring as gendered work. University of Chicago Press.

Karrebæk, M. S. (2013). Lasagna for breakfast: The respectable child and cultural norms of eating practices in a Danish kindergarten classroom. Food, Culture & Society, 16(1), 85-106.

Murcott, A. (1982). On the social significance of the “cooked dinner” in South Wales. Social science information, 21(4-5), 677-696.

Owen, J., Metcalfe, A., Dryden, C., & Shipton, G. (2010). ‘If they don’t eat it, it’s not a proper meal’: Images of risk and choice in fathers’ accounts of family food practices. Health, Risk & Society, 12(4), 395-406.

Wilk, R. (2010). Power at the table: Food fights and happy meals. Cultural Studies? Critical Methodologies, 10(6), 428-436.

Woolf, V. (1927). To the lighthouse. Hogarth Press.

- The Broons is a much-loved Scottish comic strip, created by DC Thomson in Dundee, and featuring stories about a fictional family and their antics. For those unfamiliar with the Scots language, you might need a wee hand wi’ the translation. ↩︎

- That’s your lunch or a snack when you’re away from home, in the Scots language. If you’re enjoying learning Scottish words, I highly recommend you find the poet Len Pennie, who has produced videos on the ‘Scots word of the day’ on social media such as Instagram and the platform formerly known as Twitter (as @misspunnypennie), and can be found in this interview from circa 2020. ↩︎

- Stressed as in emphasised, not as in worn out and overwhelmed with life. ↩︎

- In our defence, she’s a Great Dane, so she literally takes up a lot of space in our lives. ↩︎

- Yes, this is an unabashed homage to porridge. My excuse is that its January, its still cold and dark, and as comfort food goes, this has to be one of the better ones. Having grown up in Northern England and Scotland, it also came as part of the cultural package. While not living up to my Dad’s claims that it ‘makes your ribs stick together’, it certainly provides sustenance. ↩︎

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0